Where the Summer Ends

Karl Edward Wagner wants you to know about kudzu.

He really, really wants you to know about kudzu.

The vine gets mentioned 34 times in this 1980 short story. Fourteen times before Wagner bothers to explain what it is. In his afterward, he confesses he forgot northern readers might need a translation. It’s the literary equivalent of a Southerner assuming everyone knows what a meat-and-three is.

The story itself? Solid enough. College student Mercer ventures down Grand Avenue—a name turned ironic by urban decay—to visit Gradie, an antiques dealer who’s discovered something terrible beneath those suffocating vines. Wagner understands atmosphere. He knows how to make abandonment feel ominous, how to transform botanical overgrowth into something sinister.

And when he’s not repeating “kudzu” like a nervous tic, he can write. Look at Gradie’s introduction: the dealer emerges from his shop like “a greying groundhog, or a narrow-eyed pack rat, crawling out of its burrow—an image tinted grey and green through the shimmering curvatures of the bottles, iridescently filmed with a patina of age and cinder.” That’s not just description. That’s prophecy. The man has already been consumed by his environment, transformed into something that belongs to the ruins.

The horror, when it arrives, works precisely because Wagner has spent so much time making us feel the weight of that kudzu, the way it smothers everything beneath it. What thrives in that darkness feels inevitable.

But Lord, that repetition. Southern readers probably find the vine as annoying as Wagner’s insistence on naming it. The rest of us just want him to call it “the vines” occasionally.

Reading History

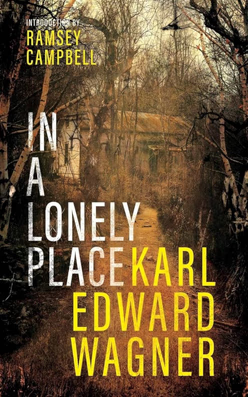

- 2025Nov9SunEbook (In a Lonely Place, Valancourt Books, 2023)

Read over 8 Days

- 2 Nov 202536%

- 4 Nov 202555%

- 9 Nov 2025Finished