In the Pines

Karl Edward Wagner takes the Gothic horror story and gives it a Tennessee drawl. The result works better than it should.

Gerry and Janet arrive at a mountain cabin. Their marriage is dying. Their son is dead. Gerry blames Janet. Gerry drinks. You know how this goes—except Wagner makes you care anyway.

The horror comes from a painting of a flapper-era woman. Gerry sees her in dreams. Then he sees her awake. The story could have been set in a moldering castle in Bavaria. Instead, it’s pine trees and local stores where you can imagine Walter Brennan behind the counter, spinning yarns about bear attacks.

Wagner’s smartest move? He puts us inside Gerry’s deteriorating mind, then has Gerry himself wonder if he’s cracking up. Both explanations—ghost or guilt—feel earned. Too many horror stories depend on characters ignoring the obvious. Wagner’s characters face it head-on.

The prose is workmanlike, occasionally stumbling (“Inside was packed more merchandise than there seemed floor-space for”). But Wagner compensates with atmosphere. The pines whisper their secrets. The locals deliver exposition with the cadence of old men on porches.

The ending disappoints. Wagner sets up what should feel like an inevitability, a trap clicking shut. Instead, he opts for traditional Gothic theatrics. It’s competent. But this story promised more—a conclusion as tight as the noose it seemed to be weaving.

Still, “In the Pines” delivers where it counts. It makes grief concrete. It makes obsession credible. It makes Tennessee Gothic.

Reading History

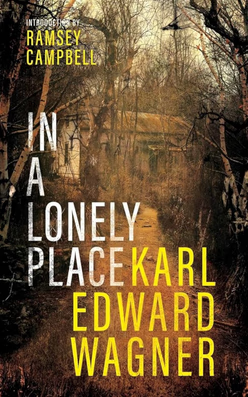

- 2025Oct26SunEbook (In a Lonely Place, Valancourt Books, 2023)

Read over 14 Days

- 13 Oct 202543%

- 26 Oct 2025Finished